There’s More to A/B Testing Then A & B: I

One of the most powerful features of mobile games is the ability to run simultaneous randomized experiments at no cost. Academics swoon at such a possibility, and it’s very real and very spectacular in F2P games. Decades of running experiments in academic research can lend insight to developer scientists. An example is an insight from experimental economics called ‘bending the payoff curve.’

One of the favorite topics of experimental economists concerns risk aversion and auction theory, risk aversion due to its ability to challenge the neoclassical paradigm (i.e., mainstream economics), and auction theory because it uses fancy mathematics. The first groundbreaking economic experiments employed auctions in lab settings to see if participants diverged from rational behavior. A series of experiments run by Cox, Smith, and Robinson15 appeared to show participants were not doing what we’d expect them to do if they were rational agents (i.e., getting the lowest price). The suggestion being participants were acting as risk-averse agents rather than risk-neutral agents. However, the critical insight came from a challenge in how these experiments were run from a 1992 AER article called Theory and Misbehavior in First Price Auctions.16

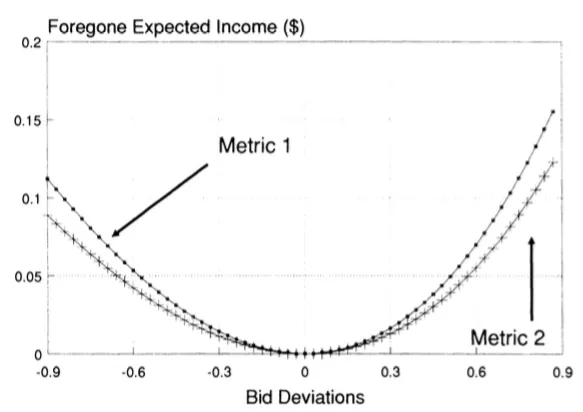

The author, Glenn Harrison, argued that the costs of engaging in non-optimal behavior were minimal. In other words, being dumb didn’t cost participants much, and being smart didn’t earn participants a great deal either. Glenn argued this casts doubt on the suggestion that participants were engaging in non-optimal behavior. Still, instead, participants weighed the expected mental effort of being innovative and concluded it wasn’t worth the foregone increase in income.

Each deviation from zero (the optimal bid) costs the participant little.

Glenn argued that what researchers need to do was bend the payoff curve, i.e., increase the reward for being smart. This way, researchers can see if their testing behavior is accurate.

What does this mean for A/B testing in my game?

Developers often turn to A/B testing to test even the most minute items; frustration emerges when results are inconclusive. For example, Supercell might test whether players prefer reward schemes X or Y in Boom Beach by way of sessions played. An A/B test that presents each scheme after a battle could be inconclusive. This is because each reward has a small outcome on player progression. That is an insight, but if we’re interested in whether A or B is better, it will make sense to ‘bend the payoff curve.’ That means we’d offer A + 5 or B + 5 to exaggerate the effects of the different reward schemes.

Think of it as amplifying two lights on each side of a room to see where flies gravitate toward. If the lights were dim, the effect on the flies would be smaller than otherwise.

See? Just like an A/B test.

While not always appropriate, bending the payoff curve is another tool developer scientists should consider when designing experiments.