A Simple Model of Cosmetics and Why They’re Hard to Sustain

In Six common mistakes when moving to live-service games and free-to-play, Ben Cousins argues that cosmetic-only monetization is a mistake:

The games that make billions from cosmetic-only economies typically only succeed because of the sheer numbers of players. On a per-user basis they actually have very poor monetization, relative to games that use more aggressive methods. This is because for a multiplayer game that is built from the ground-up to be about dominating other players, the proportion of the audience who are interested in self-expression via cosmetics is rather small.

He’s right. Traditional HD developers choose cosmetics because there are no core design implications. Designers can layer cosmetics into nearly any game at any stage of production. But for it to “work,” the game needs to achieve massive scale (low ARPU), and even still, it’s risky. It’s no wonder that very few mobile games in the top 100 grossing use exclusively cosmetics-style monetization. But I also think Ben misidentifies the challenge of cosmetics in his piece. I agree; they are certainly not about self-expression (at least the successful ones). However, male-centric multiplayer games are about domination, which is why cosmetics are viable instead of unviable.

Former “Cam Girl” Aella best sums this up by describing what it takes to get tips on stream. She writes,

Men want a few things, and probably one of the biggest is winning a competition.

You see, you’re not just trying to get a guy to pay you – you’re trying to get a guy to pay you in front of a bunch of other guys. This is a super key. A man wants to feel attention from an attractive women on him, and this is made even more satisfying when it’s to the exclusion of those around him. He is showing off his power by buying your happiness.

High-level cosmetics in multiplayer games often signal domination whether or not the cosmetic is attached to skill. Apex Legends is particularly effective at this. Consider low and high-level banners:

The stat tracker element directly shows a player’s time commitment to the game. We can also see the more exotic colors and shapes communicating danger—sort of like how the poisonous dart frog communicates danger with color.

Finisher animations are particularly humiliating since both the player performing the finisher and the one being finished must watch. It’d probably look like this if you could ever animate domination in a single five-second animation.

None of this should be shocking; we are political beings.

While these might be good observations, we need a falsifiable hypothesis about cosmetics. And to an economist, this means a model! This allows us to make more predictive statements about how a new cosmetic will or will not sell.

The Model

Consider a basic model of cosmetic demand:

\[D_i = (C_{ij} - \mu_j) P_j T_j\]

Where:

There’s much to tease out of this model. However, let’s keep it simple for this post, and instead focus on the inflation problem or what’s suggested by \((C_{ij} - \mu_j)\).

- \(D_i\) is demand for the \(i\)th cosmetic

- \((C_{ij} - \mu_j)\) is the level of differentiation of the cosmetic from the average cosmetic in circulation at that given cosmetic vector \(j\). Just think of \(j\) as any customizable “slot.” This benchmarks the cosmetic against its closest comparables in the same way you wouldn’t benchmark a goalie against a midfielder.

- \(P_j\) is the prominence of the cosmetic vector or how “featured” the cosmetic is in-game (a watch versus an entire costume)

- \(T_j\) is the amount of time the cosmetic vector is featured on screen, both for the owner and others

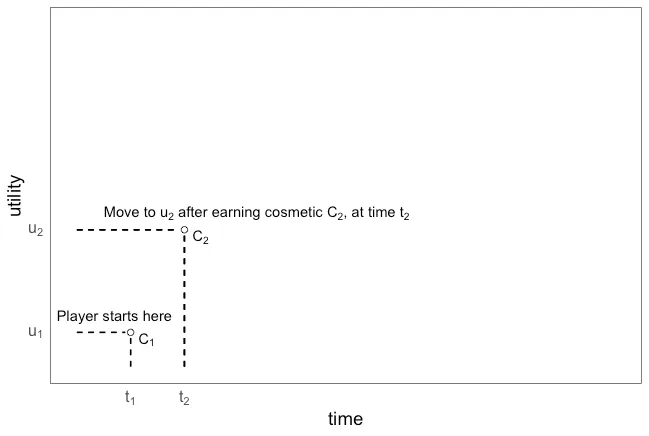

There are two elements: the cosmetics level of the game and player’s individual cosmetics level. Let’s imagine a player starting a game at time \(t_1\) and with cosmetic \(C_1\). During this period, the player derives a certain amount of cosmetic utility, \(u_1\). After earning a level, a player may unlock a higher rarity cosmetic (\(C_2\)) and choose to equip it. They move to \(u_2\) at \(t_2\) as a result.

Player Cosmetic Utility Choice Model: Getting a Better Cosmetic

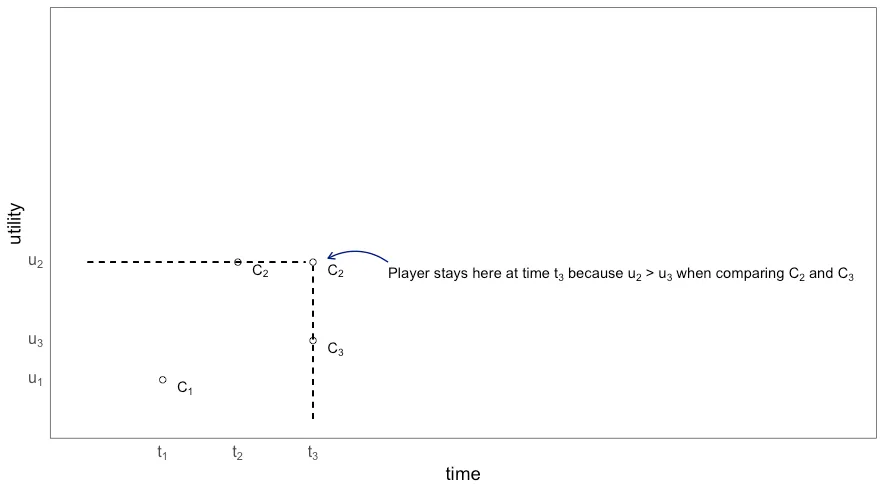

Now, let’s consider what happens when a player unlocks another cosmetic (\(C_3\)), but this time the cosmetic is of lower rarity. Because \(u_2 > u_3\) the player does not equip it.

Player Cosmetic Utility Choice Model: Getting a Worse Cosmetic

Players are benchmarking a given cosmetic against the currently equipped cosmetic in the same slot. Overtime players earn/purchase cosmetics that give them higher and higher utility. This makes it harder and harder to sell cosmetics – each one must make the player better off then the one before it. Every player in the game is going through this journey, and as such the average cosmetic level rises, just as we modeled in \(\mu_j\). And when this rises differentiation falls and with it quantity demanded. That’s a long winded way of saying that cosmetic inflation hurts monetization.

Horizontal or Vertical Progression

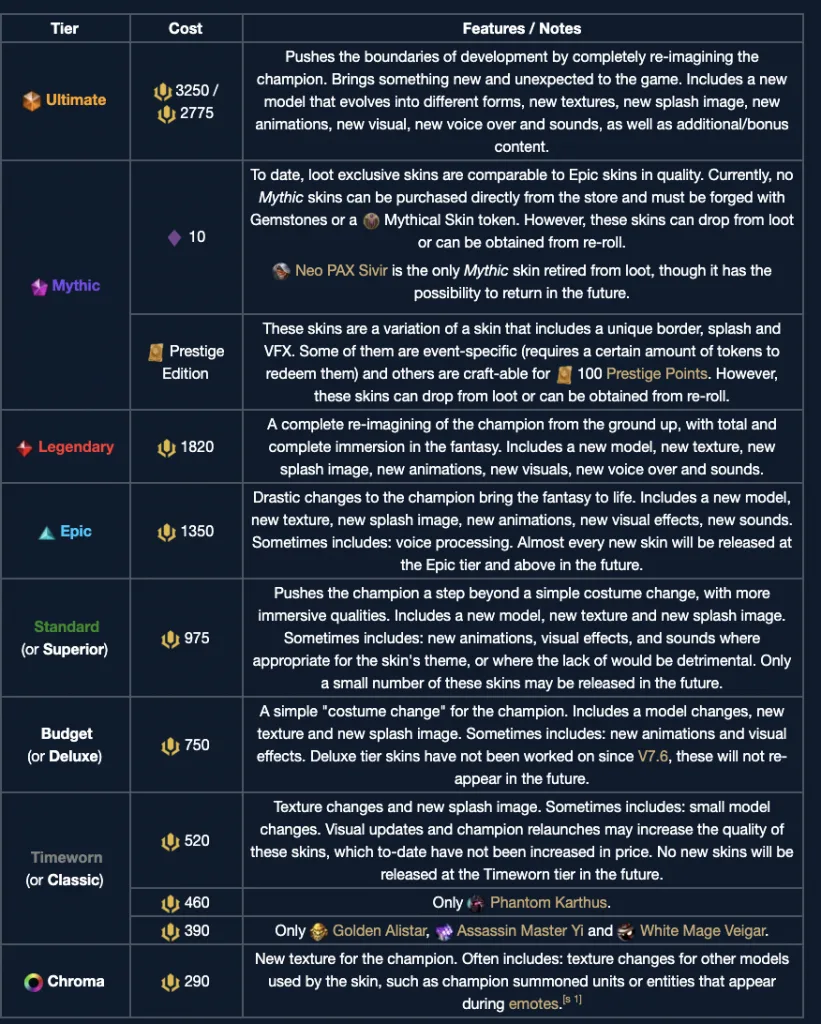

Progression is a powerful toolkit, even for cosmetics. One way to combat the inflation problem is essentially printing more money. And by this, I mean introduce higher and higher rarity. Riot, for example, introduced Ultimate II skins (3250 RP).

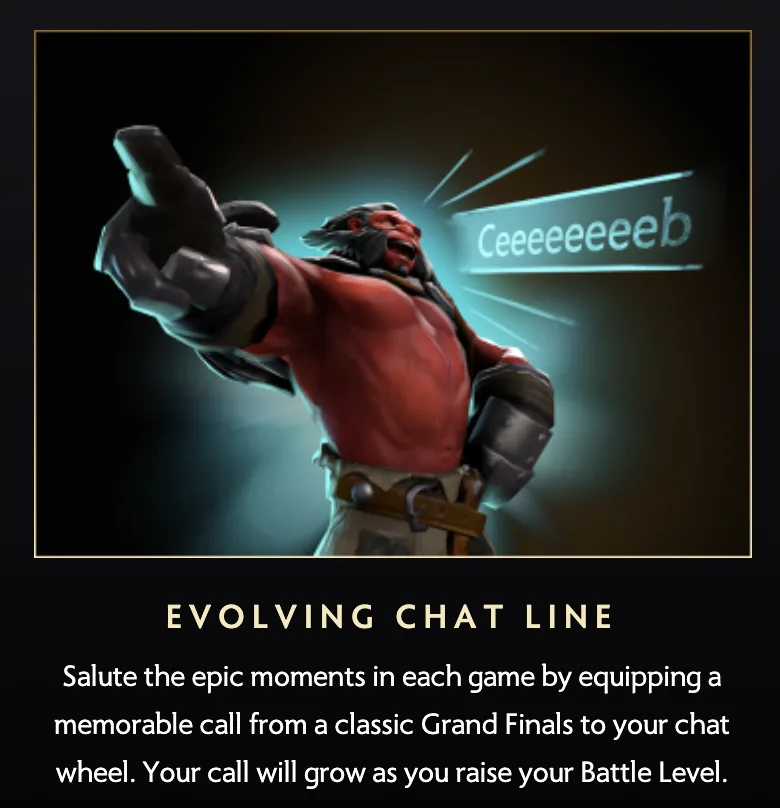

Alternatively, the horizontal way to attack this problem is to add cosmetic vectors. Dota 2 has mastered this with things like chat lines and ping cosmetics as customizable vectors. Of course, this too will face challenges when players collect more items in the given cosmetic vector.

Cosmetics is a hard road to follow, and inflation is always chasing developers. It’s essential to think carefully about mitigation strategies and how to grow cosmetic vectors over time as you would any other element of a live service.