A Quick Refresher

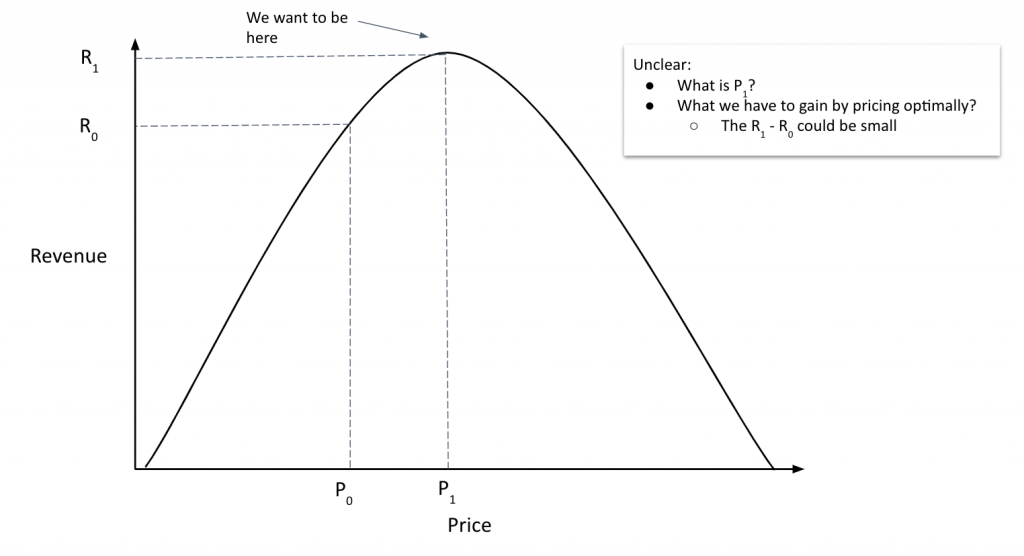

Pricing is challenging to get right. Ideally, we’d like to select a price that maximizes profit while keeping everything else constant.

Let’s add consumer surplus to the story. In the example below, this is the shaded yellow area. Some readers value the book at $30 and thus are the most profitable in the transaction ($30 – $18 = $12 economic profit). The other readers made out, but perhaps not as well.

Imagine, however, that we could charge two different prices to two different segments of readers. Say one reader valued the book at $18 and another at $30. The trick is to ensure that the good is non-tradable; otherwise, the customer who faces a lower price could resell to the higher-priced customer and pocket the difference.

While we could raise the book’s price to $30, we’d lose out on the $18 reader. The problem of price discrimination, the one described above, is fundamental to understanding entertainment business models.

Our Case

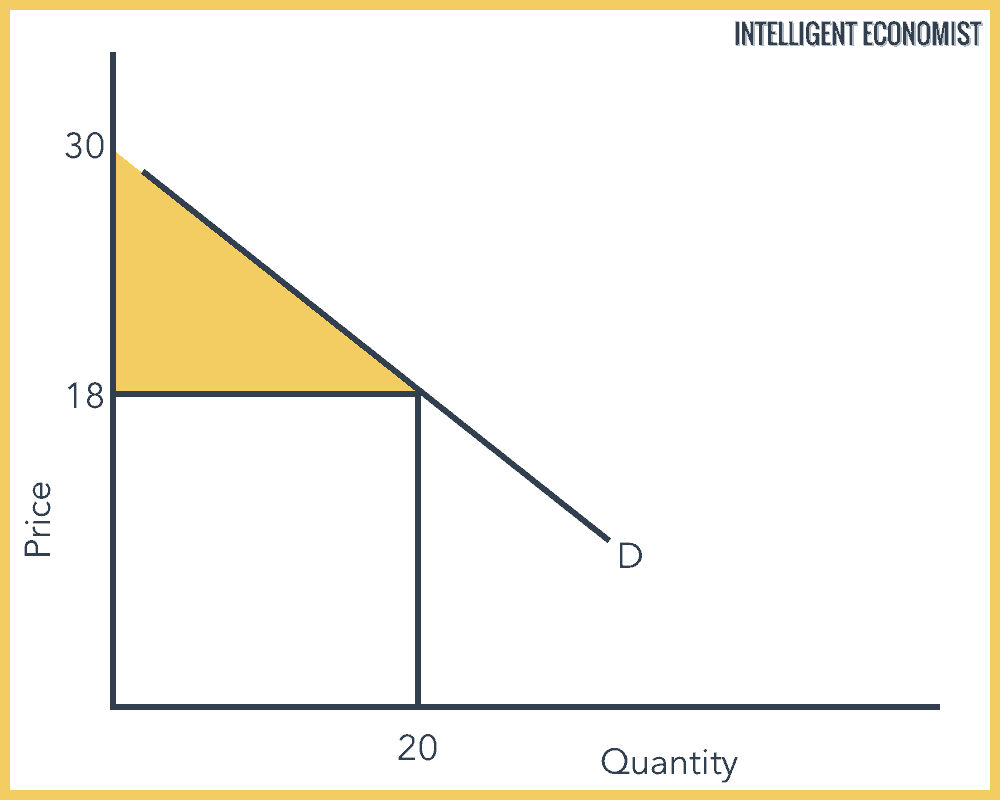

The consumer surplus model struggles to capture utility. After paying a fixed price for the book, the reader chooses to consume it (is anyone surprised?). The reader continues to accrue utility from this consumption—the enjoyment of reading the book outweighs other activities. At some point (but not always), the accumulated utility outweighs the initial cost.

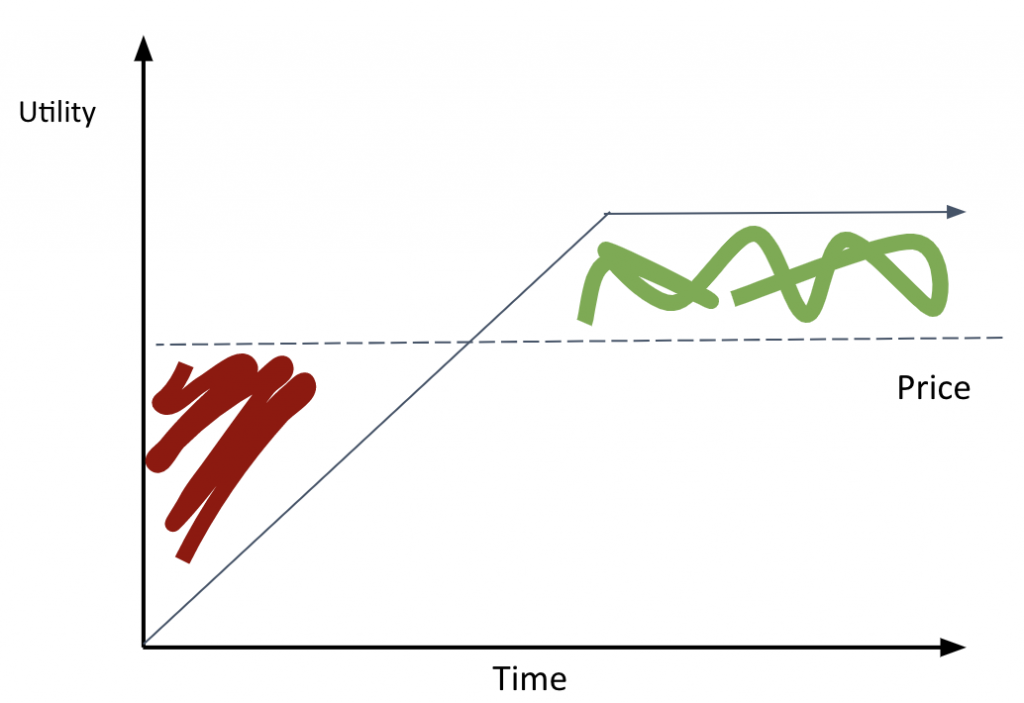

Standard Utility Curve (Reading a Book)

It’s important to note: the reader is not “in the hole” when we see red in the above graph. The book is a sunk cost; the reader should only consume it better when it’s better than engaging in other activities. But if we extend this graph to include motimeime, the curve kinks immensely.

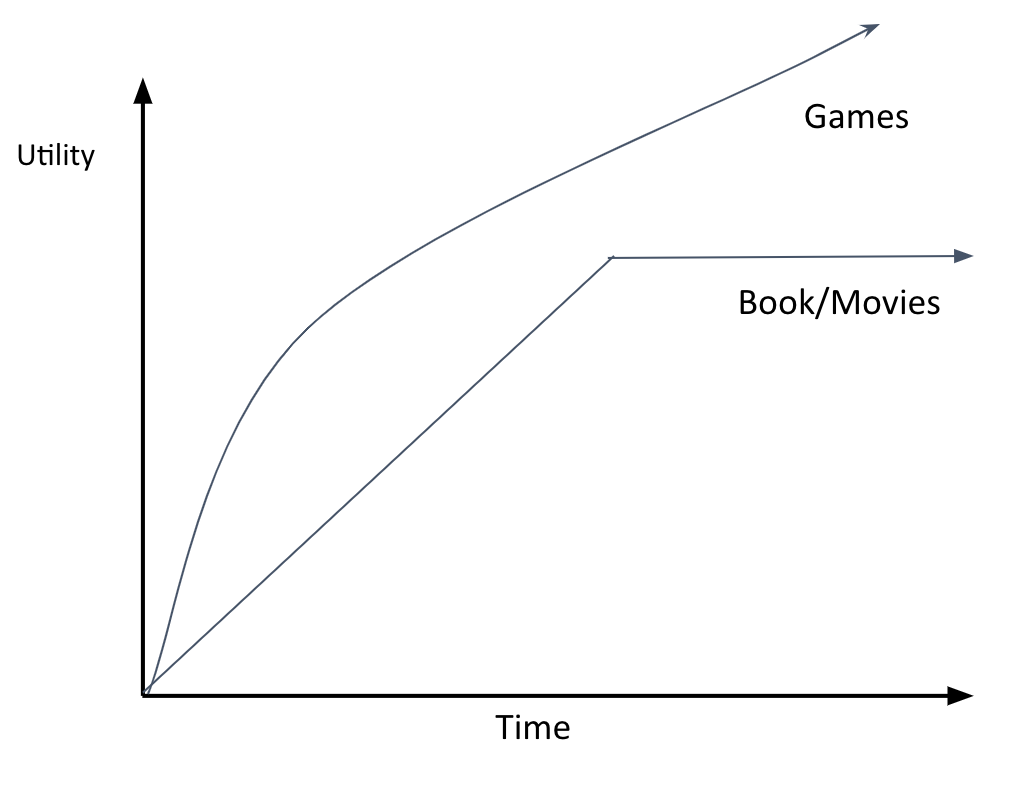

Utility Curves: Books

There are incredibly steep diminishing returns to reading a book a second time. It’s boring. Deep diminishing returns explain why book rentals (libraries) and reselling are so popular. Why pay a fixed price for what is usually a single-use item? Steep diminishing returns ring true for movies as well. Of all the films you’ve watched, what percent have you seen a second or third time? 1%? 5%? Subscriptions and rentals make sense for this form of entertainment. But what if, instead of flattening, the utility curve grew? Enter gaming.

Utility Curves: Games & Books/Movies

Games have a unique resistance to diminishing returns. As described in Part III:

The genius of PvP (Player v Player) environments is how they necessitate the emergence of a meta-game. PvP environments resemble game theory models where it has been shown strategies evolve in an evolutionary process. In mathematics, Player vs. Environment (PvE) resembles optimization where strategies are static – one and done. Each balance change reshuffles Equilibrium in PvP environments; the search for dominant strategies in an ever-shifting equilibrium is the game itself.

The strategic evolutionary process is a near-limitless piece of content to consume.

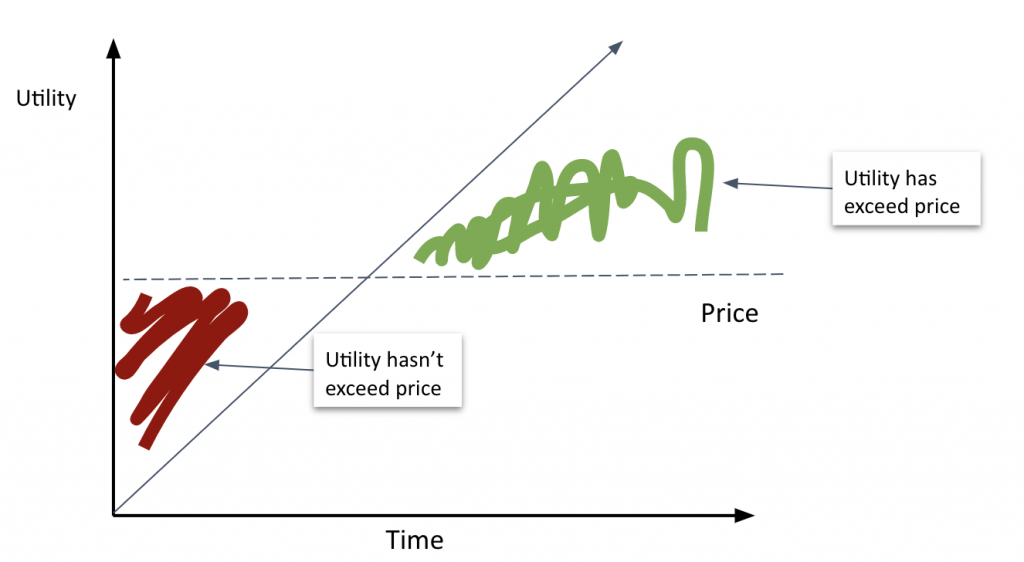

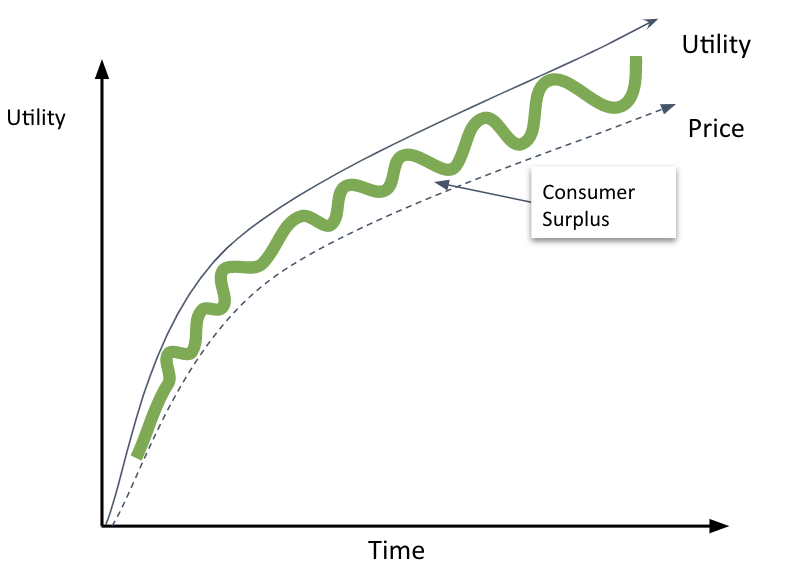

MB = MC

The efficiency of any monetization or pricing system is the degree to which it can correlate marginal cost (MC) to marginal benefit (MB). In the above examples, we fixed the price. Fixing the price makes sense, given that the utility curves flattened out. But the more the curve refuses to flatten, the more decorrelated MC to MB becomes, the longer it continues.

The above leads us to the emergence of DLC and MTX. Players were playing PvP titles for hundreds, if not thousands, of hours, and MC failed to catch up. DLC map packs like those in Call of Duty and Battlefield helped MC catch up (and grow MB!) in fixed intervals, but the correlation was still weak, and time persisted.

MTX solved for the explosion in the marginal benefit that multiplayer games were providing. Unlimited or greatly exaggerated spend caps allowed players to spend closer to their MB curves than they were previously able to do so.

Utility/Price Curve: MTX & F2P Games

Software as a service (SaaS) can generate similar growing utility but only charges a fixed price at recurring intervals. Again, this suggests that subscriptions might make sense for games. Subscriptions are better than fixed prices in correlating MB and MC, given that SaaS generates recurring homogeneous LTU returns. However, games generate a more heterogeneous LTU (lifetime utility) than many SaaS products.

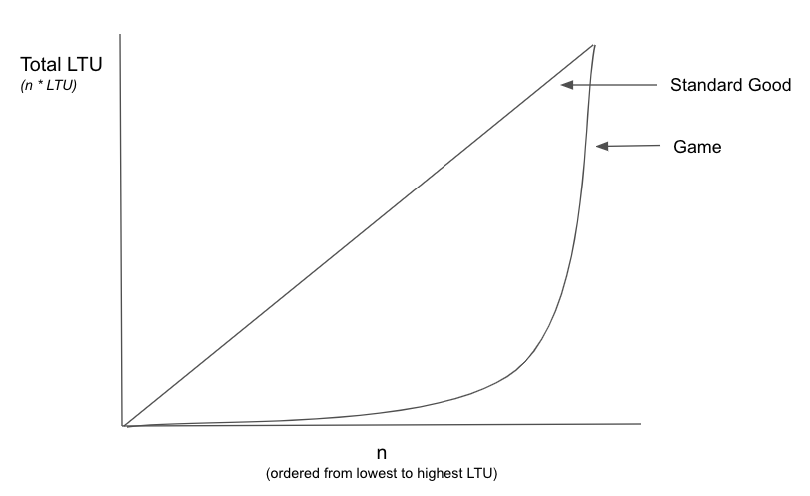

We can model the heterogeneity as such:

Considering the total Lifetime Utility generated by a standard good or game, we add up an individual’s LTU from the lowest to the highest LTU. If everyone valued a standard good the same, LTU would be linear. If a few players valued a game at a relatively extreme LTU, you would see a bowed curve – the high LTUs skyrocket total LTU upon addition. Look familiar? A bowed LTU curve correlates with observed LTVs in F2P games.

Does Tech leave too much LTU on the Table?

But that’s not to say all non-video games have a linear Total LTU curve. Some users value Zoom more than others. As Zoom usage increases, LTU also does, but the price does not. Zoom fails to capture a great deal of LTU from high-usage customers. MTX theory could offer a hand.

Zoom does offer tiered pricing for organizations, with a higher price charged for additional features, but this doesn’t capture the high LTU users within an organization. Perhaps Zoom should get into the cosmetics business—backgrounds were a fantastic opportunity never capitalized on.

Even at the organizational offering level, Zoom could create an additional tier that offers other features in addition to the high-usage tier. Multi-track cloud recording, for instance, generates incredible value for Podcasters but costs nothing further.

Standard goods and games’ dramatically different value propositions necessitate other monetization schemes. Different content economics make applying the monetization of tech companies less applicable to gaming. Instead, SaaS firms have something to learn from games.

Gaming Companies Are Not Tech Companies!