Game Companies Are Not Tech Companies Part I: Every Game Has Networking Effects, They Just Don’t Amount To Much

Ran Mo and Joseph Kim (@jokim1) argue that games should be viewed from a Silicon Valley perspective. The usual three appear: moats, networking effects, and platforms. Moreover, while I thought it had died out after the launch of Halo 3, an inferiority complex continues to exist amongst game makers. Games never seem to get the mainstream or broader tech circle legitimacy that many think they deserve. Despite operating in the Valley and major tech hubs, game companies do not reach the crazy evaluations of FAANG (ATVI has a market cap of $63B, while Facebook sits at $215B). Furthermore, public intellectuals like Tyler Cowen or Ben Thompson rarely discuss games as a part of their commentary (not with Matthew Ball, but maybe he drinks too much Kool-Aid. Even internally, game firms seem to be chasing subscriptions on the heels of Netflix and Spotify.

The fundamental problem comes from not respecting or understanding games as a distinct field. The fundamental problem comes from not respecting or understanding games as a different and unique medium separate from linear content. Kim’s piece wants to make this point in many ways, but does not go for the kill by the end of the article.

I’m writing some posts to address and expound on this. In two parts (networking I’m writing a two-sided series to address and expound on this. In two parts (networking effects & platform power), I’ll examine why game companies fall short of traditional tech companies. Then, with another two parts, I’ll address what tech companies have to learn from games (the content problem & MC = MB).

Networking Effects

Networking effects describe the positive externalities from the n+1 user to a service. Every time someone joins Facebook, the benefit increases as others can interact with that person. Gyms, for instance, work in the opposite direction: every member who joins a gym occupies a fixed amount of capital and decreases the value to each other member.

Fawning over networking effects comes from the path dependency inherent in the model: more users lead to more users. What does VC not want, sis, self-perpetuating growth? However, as Margolis and Liebowitz argued during the Microsoft case:

Although these simple numerical and algebraic examples appear both logically sound and structurally uncontroversial, these examples entail severe restrictions. The logic underlying path dependence is seductive but incomplete. […] Given that the theoretical claim that can be made for path dependency should be understood as only a demonstration of possibility, the case for path dependence becomes an empirical one.

It is not that networking effects are not real, but they are not as powerful as they were first made out to be. After all, networking effects could not save Friendster or Myspace; as we will see, they mean little for particular games.

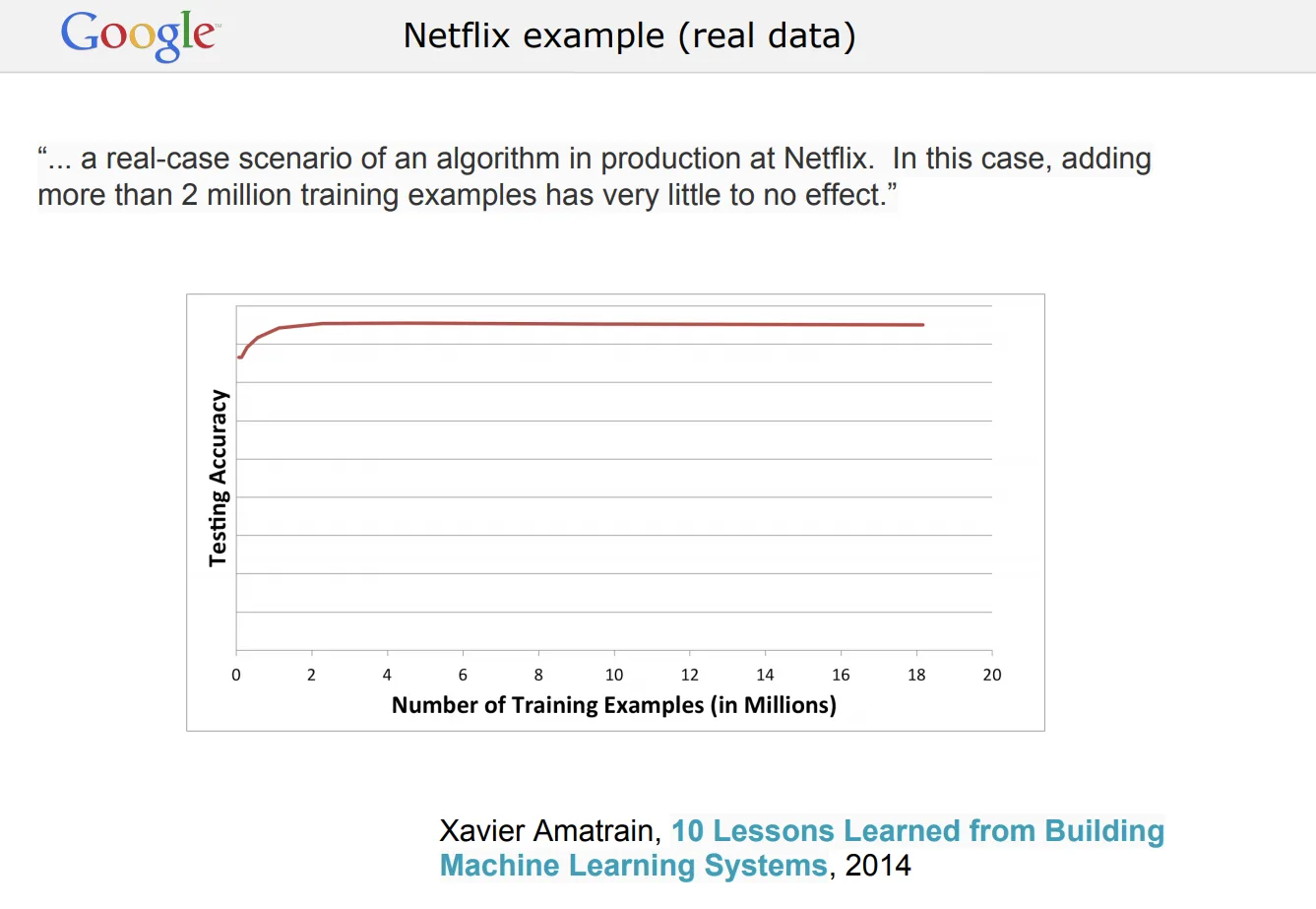

At a particular scale, diminishing returns decay positive network effects to zero. The 2nd user who joined Facebook was far more beneficial to the 1st user than the 100th million users who joined. While not directly comparable, Google’s Chief Economist, Hal Varian, makes this point regarding the predictive accuracy of models with additional data.

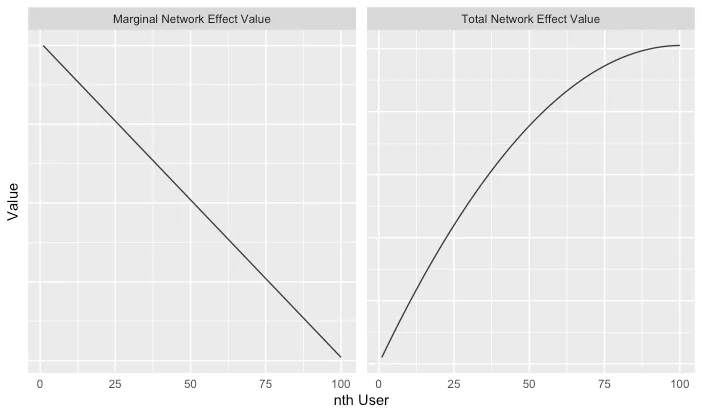

We can create a similar arbitrary model for a particular game: a diminishing network effect value for the marginal user that inevitably results in an asymptotic total network effect value.

Not all games face the same curve. A game like Hearthstone, with 1v1 play, has far less to gain from an additional user than League of Legends, which has 5v5 and many ranked segments. More users reduce matchmaking times, potential latency, and thickening skill distribution (higher P, you will be matched against similar skills). The fewer segments (modes, ranks, etc.), the less powerful the networking effects are, and the quicker the marginal value curve depresses. Cross-play doubled down on this by removing platform segmentation. Nevertheless, even for League, the networking effect power is infinitesimally small at scale; the significant gains are eaten up with a relatively low user count.

Games do not have the “sticky” elements of network effects. Synchronous consumption is another example. In any real-time game, a network effect is delivered when you play with friends. At the same time, something like Instagram Stories is consumed whenever the user pleases. It is unclear that having a friend play the same game I do is beneficial unless we play simultaneously.

Schelling’s Nobel Prize-winning work on tipping is a more apt model for describing many games today. Consider a group of players all playing the same game. These players are partially driven to play this game to be “in the know” or a part of the pop-culture conversation. Each of these players has a given threshold for defecting to a new game based on the share of public discussion consumed by the game. Players defect if the game declines as a share of the conversation; they leave as the game goes from 100% of the public conversion to 99%. More will leave at 99% and more still at 98%, continuing a downward spiral into a new equilibrium.

Of course, the inverse is true as well. Some might join a game if its share of public conversation goes from 0% to 1%, and even more would participate if it went from 20% to 30%. A new game release can set off this “tipping” chain reaction in players. Look no further than the migration of Fortnite players into Warzone. The power of tipping is as strong as “public conversation” is in player motivation. Unfortunately for developers, this means instability in the long-run capitalization of viral game hits.

I have avoided addressing two-sided marketplaces as they will more neatly fit into the next part: platform power (or lack thereof).