WTF Are These Three Battle Pass Things

When I wrote, Economics of Battle Pass Are Broken. Let’s Fix It in 2021; I argued that designers needed to play with ADMC (average daily monetization cap) to transform the pass from an engagement to a monetization vertical. Since then, every subsequent “innovation” has been a creative exercise in price increases.

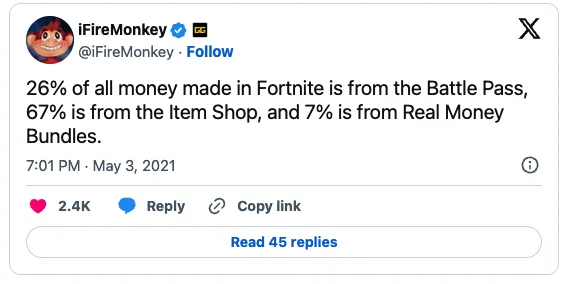

Fortnite realized this long ago, which is why the direct store has ballooned in content and uses “the vault” to sell past pass-specific content; the 67% direct store, 33% battle pass revenue split leaked from the 2012 Epic v. Apple trial likely skews harder direct store since.

Two Options: d or fc

In the original model, increasing spend depth may be achieved by decreasing \(d\) or the pass length, thereby shipping more passes over a given period.

\[\text{average daily monetization cap} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^N y_i + fc}{d}\]

Mobile games mastered this in months, using low marginal cost, fractionalized, and storable content (currencies! resources!). For example, this was the exact strategy Marvel Snap employed at launch: passes refreshed monthly, and the game was stuffed with cheap content like titles and emoji stickers. This worked at creating consistent monthly revenue bumps. While there are trade-offs in shipping slimmed-down passes (50 tiers), it’s challenging to argue Second Dinner would make 3x the monthly average if they employed the traditional three-month battle pass instead. Respawn recently tried something similar, splitting battle passes into two season parts and dividing d by two.

Apex Legends Half Season Pass

HD games struggled as the pass became a content blackhole that spits little revenue in return. While there was always upsell on tier bundles with a base pass purchase, these were applied automatically, suggesting the player only forwent the more manageable parts of the progression curve rather than the higher XP requirement at late levels.

The new proposed solution is to grow \(fc\) by adding another reward lane instead. Call of Duty’s BlackCell Pass, at 3x the cost ($30 versus $10), includes the standard pass, tier skip tokens (now as a storable currency to avoid the above problem), and ten additional rewards. It many ways, Activision just upsold a single usual $20 SKUs they’d otherwise put into the store as an entirely new pass. It’s a brilliant use of systems, wrapping content in a different monetization “sleeve” to maximize its value.

For its brilliance, Mobile employed a K.I.S.S. method, simply multiplying tiers into a new lane: another near-zero marginal cost innovation.

Three Lane Legends of Mushroom Pass (Two Paid, One Free)

Or adding multiple passes…

Legends of Mushroom Shroomie and Happy Farm Passes

The Experimentation Mystery

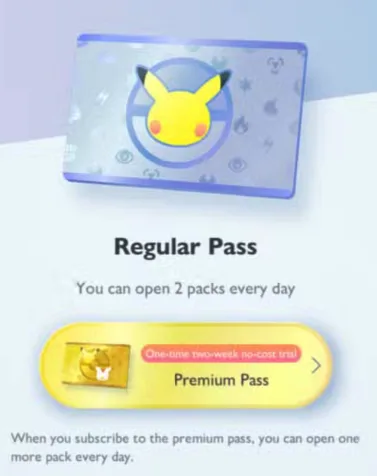

Another change has been to move the pass to a subscription: an automatic recurring charge. Fortnite implemented this in 2020 with Fortnite Crew, and while the program hasn’t died, it hasn’t precisely thrived either. Pokémon TCG Pocket is a recent attempt at this, offering an additional daily pack opening for active subscriptions on top of the typical lane system. It even boosts a two-week free “trial”!

An actual subscription seems obvious (and Apple sweetens the deal with lower tax if the player subscribes for a year or more) for battle passes, yet we’re seven years since Fortnite’s first pass, and the idea hasn’t taken off.

Analysts always praise subscription “sludge”: automatic charges that payers must actively unsubscribe to stop, and yet a neoclassical model offers more explanation. In a Beckarian view, players assess their time horizons and adjust the price for forgetting to unsubscribe, thereby increasing the “shadow price” of the pass. An easy experiment: implement the reoccurring charge but specify automatic cancellation if players don’t claim a monthly reward.

Games have also rallied around passes priced in real-world currency, not hard currency, to prevent players from earning enough hard currency from one pass to purchase another without spending real-world money. Brawl Stars did just this and was part of the platform that launched their recent wunderkind year.

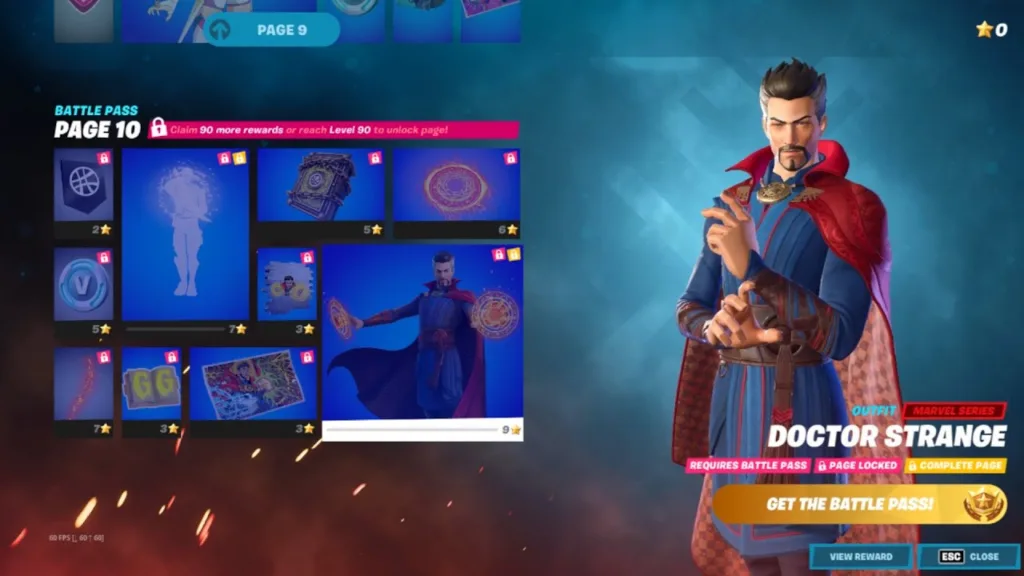

The only countervailing trend has been a shift in HD battle passes like Fortnite and Call of Duty toward “Skill-Tree”-based reward selection. In this model, players select from a pool of rewards, and after collecting a given amount of page rewards, they are allowed to choose from a newly unlocked page pool. The practical result is players’ “short-cut” toward the final reward, reducing the effort needed to reach the last rare reward.

Fortnite’s “Skill-Tree”-based reward selection

From my conversations with people familiar with those initial designs, there was no profound economic reason for the change other than a sense battle pass was becoming dull, and choice gave players agency.

I wrote my initial Battle Pass series on the premise that Battle Pass evolution was only beginning, and seven years later, the industry has woken up to the realization that Battle Pass was too expensive for too little benefit. Players cannot pay for the pass in “time”: time does not pay VC, founders, or developers, and while k-factor is real, the inability to model an LTV on top of it suggests it performs as a hand-wavy argument. The industry’s obsession with engagement metrics as a proxy for monetization potential has been an expensive lesson in confusing correlation with causation.