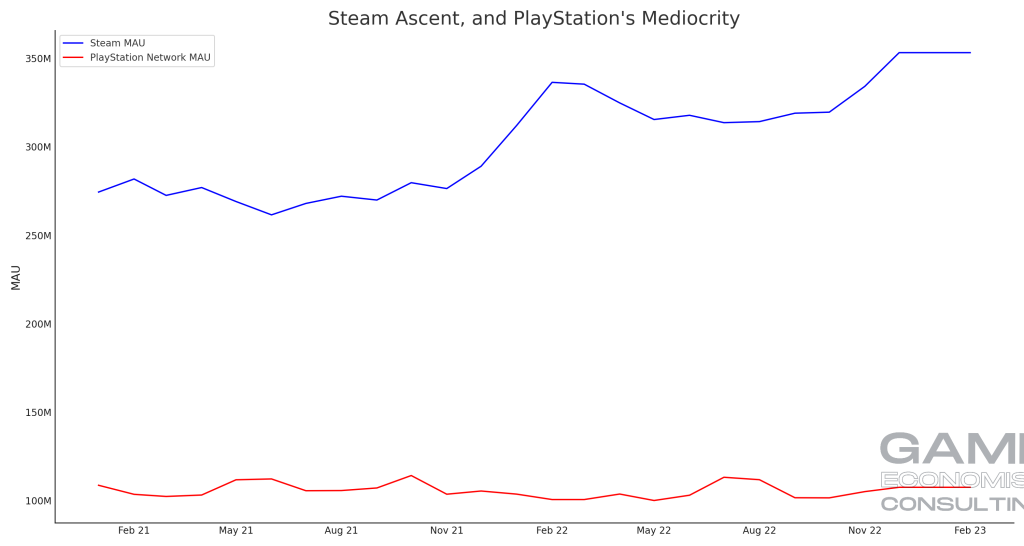

Imsominaic leaks reveal Playstation lost 3M MAU over the last three years. At a time when gaming is at its grandest heights, consoles have failed to seize the moment. Sony and Microsoft have forgotten their role as platforms, purchasing dead-end franchises instead of fostering third-party innovation. Meanwhile, Steam gained over 90M users, a ~35% increase over the same period, with Valve founder Gabe Newell downing New Zealand pies as third-party development rakes in billions as Valve barely lifts a finger.

(more…)