Arguments justifying Arcane on the grounds that “Riot can afford it” are already lost. This framing positions Arcane as a cost center. Marketing heads are commonly called “Heads of Growth” because marketing isn’t supposed to be a cost center; instead, it ought to be a profit center.

It’s a beautiful show (I loved it! Thank you for your subsidy!), and Riot can and should spend $250M on IP narcissism (they’re also a private company), but that’s different from justifying it within a cost-benefit framework. It’s a common misconception that this framework requires easily observable evidence to be useful. Instead, it asks for higher rigor and a direct answer to “How could Arcane deliver over $250M of ROI relative to the best use of investment?” The higher the investment, the more intense the scrutiny level. Another way to “grow the brand” would be to perhaps dump $250M in developer subsidies to use the Riot IP, similar to Riot Forge. The cost-benefit framework doesn’t necessarily rule out Arcane’s viability—it could suggest more investment!

Maximizing the framework isn’t easy, but it leads to optimal decision-making and long-run firm growth. Remember, Riot laid off over 500 employees earlier this year. It’s feasible a more optimized use of capital could have avoided these layoffs. Any spending has real trade-offs, and we owe it to ourselves to consider their cost and benefits.

to

know

Recent Posts

Famed Music Producer Rick Rubin said, “The audience comes last [in the creative process].” Game developers should heed this advice and avoid a “player-first” mentality. Creators must act in the best long-term interest of the game.

(more…)

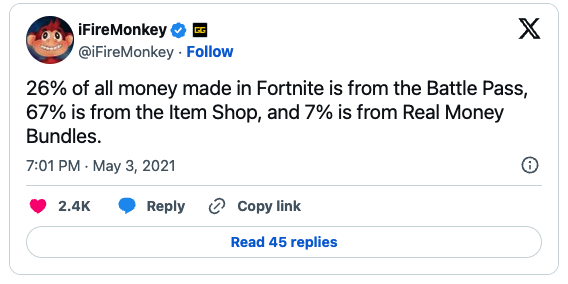

When I wrote, Economics of Battle Pass Are Broken. Let’s Fix It in 2021; I argued that designers needed to play with ADMC (average daily monetization cap) to transform the pass from an engagement to a monetization vertical. Since then, every subsequent “innovation” has been a creative exercise in price increases.

Fortnite realized this long ago, which is why the direct store has ballooned in content and uses “the vault” to sell past pass-specific content; the 67% direct store, 33% battle pass revenue split leaked from the 2012 Epic v. Apple trial likely skews harder direct store since.

Does a new Call of Duty map generate superior engagement compared to a new weapon? Which drives higher retentive effects: a new Magic The Gathering or Marvel Snap card?

(more…)

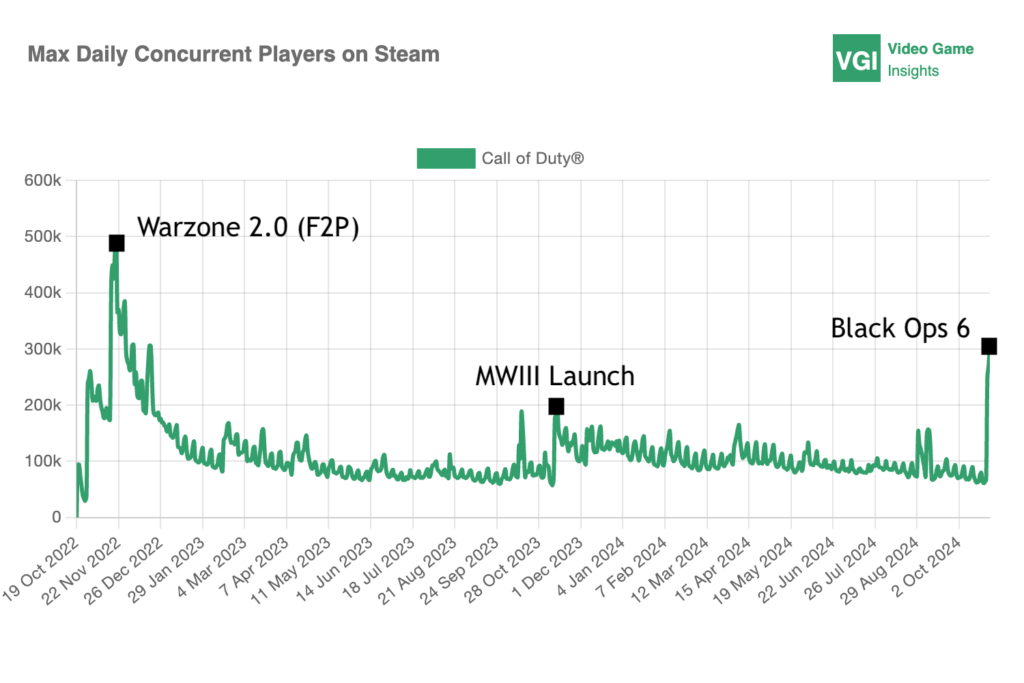

Call of Duty Black Ops 6 achieved the strongest paid Steam launch in franchise history. The franchise’s metamorphosis—from a modest war game that moved 5M units in 2003 to a cultural juggernaut shipping 20-30M copies yearly—is far more fascinating than marketing prowess—it’s a masterclass in industrial execution.

Like a Robber Baron Industrialist who strikes oil, Activision CEO Bobby Kotick’s primary innovation wasn’t in the product but in perfecting its extraction. The cascading studio system—a production architecture where three lead studios operate on offset three-year cycles—proved to be his equivalent of hydraulic fracking. Much less than “satiate” demand with an onslaught of entries, the annual releases grew demand.

Electronic Arts waited years before implementing strong support studios for Battlefield (and Apex!), and the cascading studio approach lived and died with Battlefield Hardline. The Battlefield franchise is a cautionary tale of hesitation, with Battlefield 1’s 21M copies the only time it outdid Call of Duty.

Kotick’s end-game is clear with Black Ops 6, as pieces coalesced around Modern Warfare III: horizontal and vertical franchise integration. Like Battlefield, players gravitate toward particular theaters of war, leaving them spread across different, non-monetizing franchise entries. A unified engine and single-app experience integrate the cascading model into a singular production line. This horizontal and vertical integration serves as another weapon in the Call of Duty “platform,” now functioning as a distribution center for diverse experiences: single-player campaigns, arena multiplayer, battle royale, extraction missions, and zombies—each feeding the central revenue stream.

As the game expanded, it doubled on the RPG foundations laid by Infinity Ward in 2007 to power each engagement pillar. Modern Warfare II “pro-tuning” created an almost infinite weapon permutations. Each annual entry embodied the “evolution, not revolution” mentality. However, consistent change, even if small, over many entries leaves a title nearly unrecognizable from its first entry.

Like Henry Ford’s production lines, Call of Duty has become gaming’s most robust engine—reliable, refined, and ruthlessly efficient—an anti-Ubisoft. While competitors chased innovation, Kotick proved that economies of scale are another path to dominance. While others hunted for the next breakthrough, Kotick built something far more valuable: a perpetual motion machine for manufacturing recurring revenue.

1. Distribution

The mobile “meta” is getting games in players’ hands post-ATT. The unintended consequences of Apple’s destruction of mobile acquisitions haven’t been to regain distribution control but for firms to find alternatives. “Content Fortress” ad networks, messenger apps, fake ads becoming white-lie ads, web stores, a return to brand marketing angles, and yes, web3, are all in play.

2. Distribution

See above.

3. Distribution

See above.

Joining the chorus of voices-heaping praise, Play Ventures put on a fantastic three days. Incredible event staff, an excellent venue, beautiful weather, intriguing conversations (shout out to Arya‘s team for a great fireside chat and interesting thesis), two Anton Backman jokes I’ll never forget, and sauna, of course.

FYI, it’s never seems to be “a sauna” or “the sauna,” just a “sauna” reminding everyone that this is an institution.

subscribe to the blog subscribe to the blog

subscribe to the blog subscribe to the blog

subscribe to the blog subscribe to the blog

subscribe to the blog subscribe to the blog