I have a lot to say about Marvel Snap; it’s a breath of fresh air in a mobile market that’s smelt stale for too long. Snap dedicates itself to taking advantage of mobile rather than treating it as a tax. However, for all its innovations and wins, I wonder if the Snap team outsmarted itself with a monetization model that will cap its success.

Despite structural issues, Snap isn’t far from snapping a top 20 revenue spot. But beyond the dizzying amount of design innovation and truly outstanding animation work lies a monetization system so soft it makes marshmallows blush. Instead of glaring at Hearthstone or MtG Arena (~$300m – $600M per year), Snap should set its revenue sights higher to Clash Royale’s glory years (~$700M). At ~1.5M DAU, this suggests a $1.27 ARPDAU target. That’s an extremely tall order that requires moving both the numerator and denominator.

With so much to celebrate and discuss, I split covering Marvel Snap into three parts: Game Overview + Game Economy & Monetization, Progression + LiveOps, and UX. Here I cover Game Overview + Game Economy & Monetization.

Context

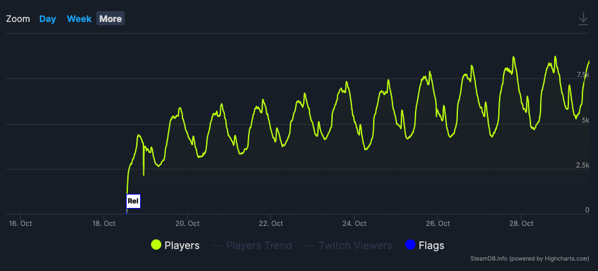

At the start of 2018, Ben Brode and Hamilton Chu packed up and left Blizzard after more than a decade each to start Second Dinner. After ~4 years of development and ~6 months in soft launch, the former Hearthstone Design Director and Executive Producer finally released Marvel Snap in Oct 2022. The Collectable Card Game (CCG) has already amassed a whopping 6m+ downloads with publisher ByteDance (see: China expansion and license), while the game’s apparent “stacking DAU” is an encouraging sign. While mobile engagement is tricky to track, Steam actuals suggest ~100k DAU against a PSU of ~8k. It won’t surprise me if Snap has already surpassed 1.5M DAUs between PC and mobile platforms. It’s probably a sign of the massive uplift developers get from macOS development. It’s a great start and suggests an extremely bright future for Second Dinner while encompassing everything Blizzard mobile should have been and will likely never become.